Frankenstein was the name of the man who created a nameless monster. Over time, the monster itself began to be called Frankenstein.

Frankenstein was the name of the man who created a nameless monster. Over time, the monster itself began to be called Frankenstein.The facetious Frankenstein analogy is a way to introduce a solemn, serious point about the church in its first 300+ years.

| The New Testament was NOT a collection of books from Matthew to Revelation; | the New Testament was Christ giving his life as a ransom for many. |

| The Word was NOT a a collection of books from Genesis to Revelation; | The Word was the Person of Christ. |

| The Gospel was NOT a type of book; | the Gospel was God's proclamation of salvation through Christ. |

- “How did we get this text?

- Who are the authors, and why did some write narratives and others letters?

- What were the logistics in using a secretary and coauthor?

- How were the books dispatched, received and used by different congregations?

- Who was involved in the collection of the Gospels, Paul’s letters, and the rest of the New Testament, and how so?

- How were the manuscripts produced, circulated and canonized?

- Why are the books arranged the way they are?

- Why are there only twenty-seven books?

- Why did it take so long to finalize the canon of the New Testament?

- How was the text preserved throughout the centuries?”

The names for most of the NT books are traditional, not inspired. Some of the epistles identify the writer, but none of the Gospels, Hebrews and a few other epistles, and Revelation do not identify their authors. Chapters didn’t appear till the beginning of the 13th century. Patzia, p. 211

Current NT verse divisions were not added till 1551 in Greek and Latin versions and 1560 for the first English version. When you read translations of early Church documents that contain chapters and verses for Scriptures, those were aides supplied by the translator.

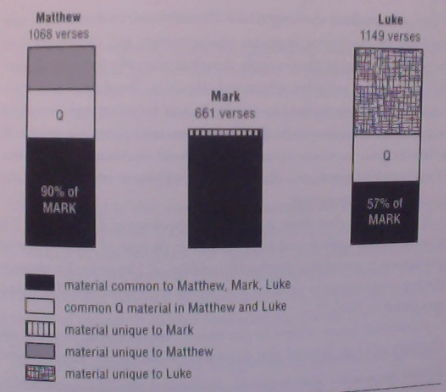

Billy Graham himself was deeply troubled by the one aspect of the Synoptic Problem, the large number of differences between different Gospel accounts of the same event. You can see these for yourselves by studying a Harmony of the Gospels.

Billy Graham himself was deeply troubled by the one aspect of the Synoptic Problem, the large number of differences between different Gospel accounts of the same event. You can see these for yourselves by studying a Harmony of the Gospels.